By: Pedro Hernandez, The Ivanhoe Sol

The national park system, known as “America’s best idea” is the United States’ largest coordinated effort to preserve both the irreplaceable nature and cultural heritage of the United States.

Now totalling 430 units, the national park system is administered by the National Park Service which serves every state and territory in the country.

Ivanhoe residents may be most acquainted with the National Park Service through Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks but now more than ever, the two most recent additions to a different side of the Service and a window to a more complete, albeit darker history of the country – overt racism and systemic discrimination.

NATIONAL PARKS TELL LOCAL STORIES

On August 16th, the Biden Administration announced protections for Springfield Race Riot Monument preserves the history of a violent attack on African Americans which occurred blocks away from Abraham Lincoln’s house and eventually led to the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

According to a press release form the White House, “The Springfield 1908 Race Riot was both a tragic event, and it was emblematic of a larger series of lynchings and racist mob violence that targeted Black communities across the United States in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Between 1882 and 1910, there were 2,503 recorded lynchings of Black people in the United States.”

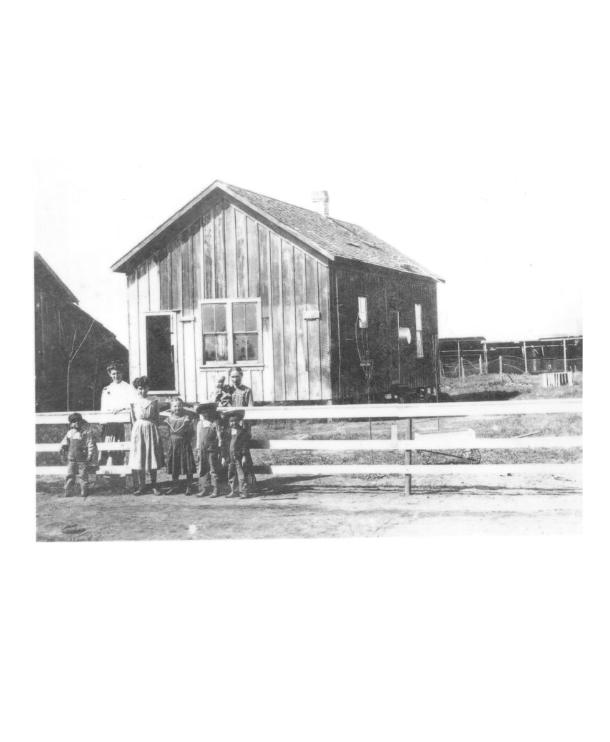

One month prior, across the county in Texas, the Blackwell School was also established as another new national park. This site tells a history of segregation of Mexican students in the small city of Marfa from 1909-1965. According to historians, segregation began in these towns starting in 1892 following the construction of a school for white students, although there was no state law that mandated separate schools. On this site, students were punished for speaking Spanish and under-resourced in their education until their integration into the Marfa Independent School District.

LOCALIZING HISTORY

While these stories may seem abstract or far away, similar occurrences have taken place in Tulare County and nearby cities like Fresno, Bakersfield, and Visalia.

One of the first major events that established the ideology of white supremacy and racial segregation in the area known as the San Joaquin Valley was the displacement of the Native Yokuts and other people indigenous to the region who were forced into Indian reservations. This practice also inspired the World War II-era internment of Japanese residents where an estimated 5,000 people we help on the grounds formerly used by the Tulare-Kings County Fair.

While there were various historical events such as colonization of California by Spain, most of the direct removal native peoples resulted from the United States government. Motivated by ideas such as “manifest destiny” – a belief that the expansion of the United States through the entire continent was inevitable and justified – as well as the economic opportunity provided by the Gold Rush, development of railroads, and the profitability of agribusiness, a new social era descended on the region in the late 1800’s.

Although segregation was eventually outlawed in the 1954 Brown vs Board of Education Supreme Court decision, this practice was prominent in California and Tulare County history as demonstrated by the “Visalia Colored School”.

The Visalia Colored School preceded the eventual founding of the Visalia School District in 1885, which currently includes and represents Ivanhoe Elementary School.

This school district was also the site for one of the earliest legal challenges against racial segregation.

LEGACY OF INEQUALITY TURNED INSTITUTION FOR RESILIENCE

Edmond Edward Wysinger, a former slave who purchased his freedom for $485.90, was one of the earliest African American settlers in central California. After the Visalia School refused to admit his son Arthur, Wysinger challenged the school in the Tulare County Court, eventually losing.

Undeterred, he took his case to the California Supreme Court in 1890 where it was decided that segregation based on race was illegal. This case was also one of five cited in the pivotal 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education that ruled racial segregation of schools was illegal across the country.

While many formal practices of racial segregation were increasingly outlawed, communities like Tulare County were home to some of the most prominent white supremacist cultures in the United States, notably demonstrated in the 1931 Ku Klux Klan state convention hosted in Visalia.

Yet as one of the largest institutions that serves Ivanhoe, VUSD has served as a community anchor in preserving the victories of civil rights advocates. Over the years the school district has served as a resource for free and reduced cost lunches, education opportunities, a meeting space for community forums, even providing resources such as wifi hotspots in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, the school district has directly contributed to mitigating social inequities like poverty to some degree and has provided upward social mobility for many.

These resources are now reaching communities of color at some of the highest rates in Tulare County history. For example, across its nearly 40 individual sites, VUSD has a minority enrollment rate of nearly 80 percent. In addition, Ivanhoe Elementary has a minority student population of nearly 97 percent where 90 percent of all students identify as Latinos and where 60 percent of the students are identified as English learners.

Not without controversy, the VUSD has remained under close examination by some parents and organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). This organization has issued several legal challenges bringing reform to VUSD to address anti-gay harassment and a 2018 suit alleging racially disparate rates of detention and suspension toward students of color.

However in many ways, this tension between addressing a national legacy discrimination and the persistence of those in search of equality is one way we keep our histories alive. And to that degree, this ebb and flow towards justice is one of the most American traditions we enact every day.

Comments are closed.