By: Pedro Hernández, Ivanhoe Sol

On December 12, the Tulare County Board of Supervisors considered the adoption of the new Environmental Justice Element to the General Plan. This marked the culmination of a multi-year process to collect public input to develop new policies.

For readers unfamiliar with planning jargon, the “general plan” is a set of local policies that set in law the authorities of local agencies like the County of Tulare and direct actions to meet certain goals such as economic development, safety from flooding, improving environmental pollution, and affordable housing.

In 2015, SB 1000 passed in the California Legislature which created the mandate that set in motion the requirements for cities and counties to either develop an environmental justice element or revise existing policies to incorporate environmental justice considerations.

Specifically, this policy initiative arose from the many cumulative pollution burdens, environmental injustices, that have been created from disproportionately locating polluting industries near and within low-income communities. These policies are relatively new in relation to the 1973 Tulare County General Plan that identified over a dozen low-income rural communities that were not deemed worthy of county investments.

HOW DOES IVANHOE RANK?

In total, this planning effort identified 48 distinct disadvantaged communities within Tulare County, including Ivanhoe. Under the categories defined by law, Ivanhoe counts as a “disadvantaged community” for both its average income falling below state average and its overall cumulative environmental burdens as according to the state planning tool, CalEnviroScreen.

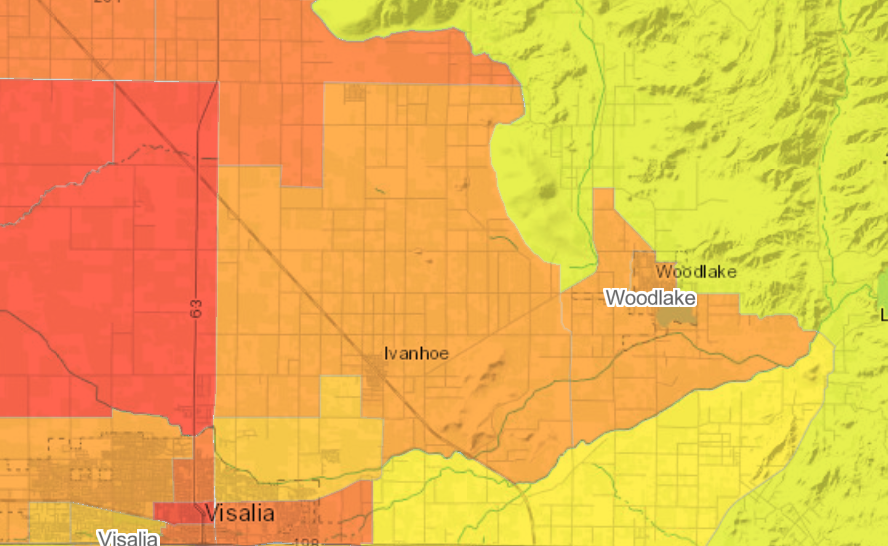

The CalEnviroScreen tool places Ivanhoe’s cumulative community vulnerability at the 77th percentile, meaning that only 23 percent of California’s communities have a higher cumulative pollution burden.

(Caption: CalEnviroScreen and Ivanhoe region. Source: CalEnviroScreen 4.0.)

However, for individual environmental vulnerability factors, Ivanhoe ranks higher than nearly all California communities on issues such as ozone pollution (94th percentile), particulate matter pollution (92nd percentile), impaired drinking water quality (96th percentile), and pesticide exposure (89th percentile). In regards to social vulnerabilities, Ivanhoe has high rates of linguistic isolation (85th percentile), unemployment (94th percentile), and poverty (89th percentile).

In June of 2023 the Tulare County Resource Management Agency hosted a listening session to identify the needs of the Ivanhoe community. According to the results, many of the community members were concerned about clean tap water and access to local parks, making up around 36% of the responses. The least of their concerns was public transportation and civic engagement, making up around 15% of the responses. Most of the participants expressed that their community would benefit from having more police departments and cultural centers.

Data from the Environmental Justice Element also found that in the last 10 years, Ivanhoe has had some of the highest rates of pedestrian and bicycle collisions in Tulare in comparison with other communities like Cutler-Orosi, Strathmore, East Porterville, Terra Bella. Most of these accidents occur on arterial streets, where there is a higher probability of pedestrian and automobile contact.

WHAT DO THE NEW POLICIES INCLUDE?

Environmental justice (EJ) is achieved when a fair balance of environmental burdens is shared across all communities regardless of income, ethnicity, race, or any other demographic. California state code defines EJ as “the fair treatment of people of all races, cultures, and incomes with respect to the development, adoption, implementation, and enforcement of environmental justice laws, regulations, and policies.”

As such, a General Plan’s EJ policies must reduce the unique or compounded health risks in disadvantaged communities by doing at least the following: reducing pollution exposure, improving air quality, promoting public facilities, promoting food access, promoting safe and sanitary homes, promoting physical activity, promoting public engagement in the public decision-making process, and prioritizing improvements and programs that address the needs of the disadvantaged communities.

Some examples of policies in the final Environmental Justice Element include:

CARP EJ-1 Policy: “Limit the impacts of climate change on the most vulnerable populations by focusing planning and intervention in and with communities with the highest need. This can be implemented by ensuring that policies, services, and programs are responsive to community members who are most vulnerable to the potential impacts of climate change.”

EJ-2 Policy: “The County of Tulare will collaborate with community members within Environmental Justice Communities to best determine and address the unique needs of each individual community.”

THE HEARING

While there were no Ivanhoe residents in attendance, there were several members from disadvantaged rural communities in Tulare that provided comments to the Supervisors.

Mary Hightower from Matheny Tract discussed the need to protect the community from two nearby factories that have a high volume of polluting trucks. Mary Wade, another Matheny Tract resident who had lived in the community for 75 years, said, “We’ve dealt with pollution for years…and we really hate that there will be more impact upon us. We hope something can get done.”

Ashley Vega, Tulare County policy advocate with Leadership Counsel – a local advocacy organization that works with rural communities, said “the County’s historical land use practices have resulted in in over 35 disadvantaged communities that bear the brunt of pollution burden from sources such as pesticides, agricultural operations, food processing, dairies, industry and transportation all while experiment a lack of investment needed to build healthy communities.” She claims that the proposed general plan does not adequately address pollution from pesticides diaries, water contamination, and industrial land uses

According to Vega, the proposed policies do not adequately ensure accountability. She said, ‘The policies that are included will not result in meaningful action because they lack binding language, implementation measures and police, and limit actions to feasibility….The county’s EJ element must take initiative.”

Often, policy discussions revolve around specific words. One example of such an allegedly loose policy directive includes a policy specific to Ivanhoe which states, “the County shall encourage the development of parks near public facilities such as schools, community halls, libraries, museums, prehistoric sites, and open space areas and shall encourage joint use agreements whenever possible.” According to community members, phrases “shall encourage” and “whenever possible” do not provide explicit intent as other phrases such as “must encourage” or “will encourage.”

Emma de La Rosa, another Leadership Counsel advocate, raised the issue that action was needed because many residents cannot relocate. She spoke on behalf of a Pixley resident named Josefa and said, “We’ve heard comments that if we don’t like it here then we can leave, but we can’t leave. Maybe it;s easy for you to say because you have the money but for us it’s not easy. We don’t have the funds to just get up and leave.”

In total, about eight Tulare County residents provide comments concluding Maricela Mares-Alatorre, an advocate with the Community Water Center who encourages the Supervisors to be as responsive as possible to community concerns. She urged, “as long as the decisions that are made still impact vulnerable communities it doesn’t matter how wonderful your use of public participation is, please listen to the communities and make decisions that will result in a healthy environment for all.”

In response, County staff responded that some of the demands from Leadership Counsel and community members were unreasonable and would negatively impact the Tulare County economy.

As the discussion of the Supervisors ensued, Supervisor Eddie Valero asked “is this a living and breathing document, by saying that, can these change according to community needs in the future?” County planner, Aaron Boch, responded that “these policies themselves are very new to the sound so this is a first step and moving forward as we do update the general plan and I’ve used this with the Attorney General and Leadership Counsel, when we update the general plan in 2030 well update a lot of elements but I think absolutely that time it’d be a good time to change these but we do try to review all of our policies at least every five years.”

Valero who represents 13 unincorporated communities responded, “I personally see this as just the beginning and yes this is in front of us to take action and we’re taking an action today but know that this as gong back to what Aaron just said this is a living and breathing document that we well set as the gold standard for us to move forward to in the future.”

While the supervisor discussion did not directly address community issues pertaining to issues such as pesticides or air pollution, Supervisor Van der Poel and Micari did raise several examples including sidewalk projects as a prior the county prioritized the development of disadvantaged communities. To this effect, Supervisor Valero closed the discussion with an example in Ivanhoe which demonstrated his commitment to building healthier communities.

Regarding the proposed sidewalk project on Road 160 he said, “that project has been long in the making, I would say in what from three years in terms of trying to get from start to finish and there are some community members that would call me and say ‘no I don’t want this sidewalk in front my home.’ And it wasn’t until a group of us, residents and myself, who had to go up and talk to those residents and explain to them the need and explain to them the purpose and the why of this project. And thankfully some of the residents were willing and said ‘to better the community I will.’ I hear all the concerns and it’s just making sure we are putting laser-like focus on these communities but taking the time to build those relations and communicate.”

Prior to a final decision, the county Supervisors went into “closed session” to meet candidly and discuss items of concern with their lawyers and staff. No further public discussion ensued and after a motion by Supervisor Micari, the board voted unanimously to adopt the environmental justice element.

Comments are closed.